- Home

- Margaret Mahy

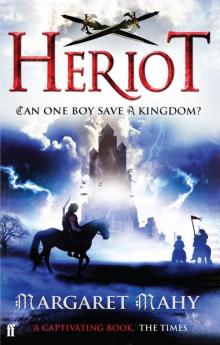

Heriot Page 5

Heriot Read online

Page 5

‘Oh, I’d definitely say you were recognised, wouldn’t you, Cloud?’ Lord Glass fluted cheerfully, lifting his eyes from Heriot’s stricken face.

The long lips parted. ‘He recognised me,’ said Cloud in a very soft voice, little more than a whisper, touching the corner of his eye reflectively as though minutely adjusting his vision, and then falling silent again.

‘It is the recognition, you see,’ said Lord Glass. ‘I understand your boy has not left the farm, and Cloud will swear, moreover, that they have never met, for he has never once been here. And yet apparently the boy described him in detail, and news of that description has seeped over to the old battlefield.’

Great-Great-Aunt Jen looked around the circle of faces as Wish came up from the stable and stood behind the women and children.

‘Someone has been talking of Heriot’s illness,’ Great-Great-Aunt Jen said to him. ‘I hope it was no one in our family.’

Lord Glass signalled to Dr Feo and Cloud, dismounting as he did so. ‘People will do it, Jenny, they will do it,’ he said cheerfully.

‘The boy’s mother had better be sent for,’ said Great-Great-Aunt Jen in a resigned voice, and gave Heriot’s shoulder a reassuring pat. ‘Baba, get your mother, will you? Wish, it might be a good idea to call Radley in. Come, my Lord. Will your companions come with you?’

‘Oh, Feo will. I may need him, and somehow I think it would be hard to keep him out,’ Lord Glass replied. ‘He’s such an enthusiast. Now Cloud would prefer to stand here by the door, wouldn’t you Cloud? He’s a very observing creature – and his presence always makes people think, you know, and to my mind that’s always a good thing, particularly out here in the country where we can easily become so casual.’

‘Anna,’ Great-Great-Aunt Jen cried as Heriot’s mother arrived from work in the still room, wide-eyed and anxious. ‘Don’t worry, Anna. Nothing’s wrong, but come to the big room with us. Baba – will you and Joan bring wine and cakes.’

Lord Glass, following Great-Great-Aunt Jen, marched through the house into the big room with a self-confidence Heriot resented. He promptly seated himself at the head of the table, inviting Great-Great-Aunt Jen, with a courteous wave of the hand, to sit in one of her own best chairs, and pointing Dr Feo to another. His smoky eyes flitted with curiosity over the glass lamps and the carved chests where curtains and blankets were kept folded in dried camphor and lavender. Baba and Joan carried in trays of glasses and goblets.

‘Very nice, Jenny,’ Lord Glass said. ‘Oh, it warms my heart to see that you have fallen on good times. So well-deserved too! And now, Heriot, you’re not the first person we’ve met who is reputed to have had a vision. Feo here is quite an expert on visions, so I want you to tell him everything you can about yours, particularly what it felt like. And, in return, Feo may be able to help you to understand what happened.’

‘Speak up, Heriot,’ said Great-Great-Aunt Jen. ‘There’s nothing to be afraid of.’ But she was frightened herself, even as she said this, so it was not in her power to comfort him.

Dr Feo was a slender, stooped man with a grimacing smile that curved his lips down rather than up. He had very long, well-kept hands. He smiled at Heriot now, folding these hands one over the other as he prepared to listen. Heriot, speaking into the space between Dr Feo and Lord Glass, began telling the story of his courtyard vision. Born on a farm he had often seen blood, for animals were always being killed and cut up for food but, as he recalled Carron’s face and his lively lips spilling words and blood with equal passion, he stumbled and grew silent, putting his hand over his left eye, his puzzled one, to stare hard at Lord Glass for a moment before he dropped his hand and looked at the floor again.

‘Well, Feo?’ said Lord Glass. ‘Is this child a Magician of Hoad, or is this another wild-goose chase?’

‘How could he be a Magician of Hoad?’ asked Heriot’s mother. ‘The Magicians of Hoad are madmen … so empty of themselves that something else talks through them. That’s what we hear of Izachel, the King’s Magician.’

Lord Glass saw Heriot glance at her, and read something in his expression.

‘A good point!’ he agreed. ‘Izachel is a Magician, and like most Magicians … he gives mysterious and enlightening utterances … he reads the minds of other men and tells the King what he reads there … but at the same time he’s an idiot in almost every ordinary way, a prophetic doll. Of course, having said that, there are at least two exceptions in our history. The rational Magicians of Hoad. And great blessings they have been to the Kings for whom they worked. Now it is possible, just possible, that Heriot might be a rational Magician. After all, he’s one of your people, and you are like the Orts, the ones you call the Travellers. You are all descended directly from that ancient people, the Gethin, the ones who lived here hundreds of years ago … the ones waiting for us when we first landed here. Now I am a King’s man, and I have to follow all possibilities, no matter how remote. Feo – you have studied the Magicians of Hoad, including Izachel, for years. I need your opinion.’

Dr Feo sat Heriot in front of him, took his wrist, laid cool fingers on his pulse and began to question him about his vision. Had anything like this ever happened to him before? How did he feel afterwards? Did the figure of Cloud appear quite solid or could he see through it? He stared with large, melancholy, hazel eyes deep into Heriot’s own eyes, and then asked him to look into a crystal, to breathe some smoke from leaves, burned in a bowl, and then to watch a silver pendulum swing backwards and forwards.

When the pendulum stopped, Dr Feo turned to Lord Glass.

‘There are some characteristics,’ he said cautiously. ‘There’s certainly a discontinuity in the flow of his awareness … a jump of some kind, as if something else was pushing in on him. And he might not know it, but he watches the pendulum and me simultaneously. It’s worth pursuing.’

‘Well, I can’t read what you call awareness but I can read faces,’ said Lord Glass. ‘Jenny, Dr Feo is very excited at the prospect of working with your great-great-nephew.’

Dr Feo smiled politely, and looked at Heriot with a benevolent expression, in which there was a hint of something that was not at all benevolent.

‘What are you going to do about all this?’ cried Heriot’s mother.

Lord Glass gave her a smile that was all his own – sweet and yet without kindness.

‘We’re merely messengers, my dear,’ he said, ‘sent to convey Hoad’s interest …’ Lord Glass hesitated, ‘and Dr Feo has just told us your boy is worthy of the King’s interest. Apparently he is very promising.’

‘For what, my Lord?’ asked Heriot’s mother, the very question Heriot was secretly asking too.

‘Who can say, my dear? But do not take a sombre view of things.’ Lord Glass waved his hand, then, drawing off his gloves, he poured wine for himself and Dr Feo, from the family bottles displayed, along with goblets, on a long shelf, choosing to drink from the most elegant goblet. ‘Now be honest … er … Anna, is it? … May I call you Anna? … Ask yourself what there is for anyone with his apparent talents here. Country life is wholesome and charming in its way … but it is limited. Mind, I’m not criticising, but I believe he will come to be grateful to the chance that takes him to Diamond.’

‘Well,’ said Great-Great-Aunt Jen, ‘you still owe us some explanation, my Lord. Why take him? We’re not under obligation. We’re not at war.’

‘Come now, Jenny,’ Lord Glass said, holding his goblet up and looking at her over the top of it. ‘Think of El-El, or Zazareel, or more recently, Izachel – think of the mysterious part Magicians have played in our lives over hundreds of years. A Magician is a treasure to a King, and any Magician automatically belongs to Hoad the King, so your boy will come to Diamond and make his fortune. Because of course, as even you may have heard, even Magicians age and Izachel is no longer reliable. Our King really needs a Magician and your boy may very well do.’

It was at that moment Heriot truly understood he was going to be taken

away from the Tarbas farm, from the kitchen courtyard and garden and from the unfolding fields of the farm. It was then he truly understood that his own wishes would not be consulted. At that very moment Lord Glass said, ‘After all it isn’t for you to decide, is it, Jenny? Just suppose you were to beg me to leave him be, and just suppose I gave in, not that I would, for I’m not nearly as benevolent as I try to make myself appear, all that would happen would be that someone less talkative but very much more unpleasant would wait on you. You would suffer, the boy would suffer, and I would suffer, too, for my hesitation. There is no decision to be made beyond Feo’s and his decision has been made.’

Heriot looked up, his hands clenched together before him. ‘Don’t I get asked?’ he cried abruptly, and Lord Glass turned to him, surprised and shaking his head.

‘My dear boy – certainly not!’

Heriot turned, not to his mother, but to his Great-Great-Aunt Jen.

‘Don’t let them take me,’ he cried.

‘I have to,’ she answered.

‘Why?’ Heriot asked her, and felt something gathering thunderously in him. Once again a storm was on the way. Once again he thought he might be about to crack in two. ‘I don’t want to go with that Cloud,’ he exclaimed furiously. ‘I’m frightened. Frightened sick!’ He sounded angry rather than frightened, but all the same, within himself he was terrified. Same old fear, said a voice somewhere in his head. Drive it out! Get rid of it!

‘Don’t shout, Heriot,’ Great-Great-Aunt Jen was saying sternly. ‘Be brave. Face up to it. I can’t help you.’

‘Do I have to help myself then?’ demanded Heriot.

Something moved behind his eyes as he turned to look at Lord Glass. Something in a private space in his head looked out of him. But to use the talents of whatever it was that lay on the other side of the fracture, he had to acknowledge it.

‘You’re all changing me,’ he cried desperately. ‘You’re making me change.’ And he began to tremble … nor was he the only thing that shook, for the glasses on the tray shuddered along with him, softly at first and then with an added clamour. The wine spiralled up the sides of the goblet and the goblet itself danced and spun on its round foot flashing sparkles of light across the walls and ceiling. The slender jug danced on its tray, the windows hummed, each one on a separate note, but in disturbing harmony rising higher and higher, until Heriot’s teeth ached with the sound. Great-Great-Aunt Jen looked around wildly, his mother raised her head and stared at him incredulously, but both Dr Feo and Lord Glass now seemed to recognise him beyond all doubt. The glasses chattered on in shrill voices, the goblet sang and signalled, the jug burned, the windows hummed higher and higher, until they were screaming, pitched on the very edge of possible hearing, and then suddenly everything in the room that was made out of glass burst into clear splinters. Heriot felt his eyes turn back in his head, and his eyelids close over them, like curtains drawn over windows through which too much might be seen.

Dr Feo caught him and held him tightly, even patting him as if he were a good dog who had done well.

‘Just see how radiant Feo looks,’ said Lord Glass in a voice that contrived to be shaken, querulous and somehow entertained as well. ‘Now I would be very annoyed with anyone who treated my treasures like that, but Feo has it in his power to forgive all, though of course in this case, it is not his own property that has been harmed. Feo? You’re pleased, are you?’

‘Oh yes, my Lord,’ said Feo, sounding excited. ‘I think the boy made powerful use of some despair …’ he coughed apologetically. ‘I would surmise, that he wanted to strike at you, but he realised that, if anything happened to you, his family might suffer, so he attacked, we might say, by association.’

‘Might we say that?’ inquired Lord Glass, arching his brows.

‘The glass!’ said Dr Feo eagerly. ‘Not another thing was touched, only the glass. I think it might be a play on your name, a sort of pun.’

Lord Glass sighed deeply. ‘There are people who suggest that, now the wars are over, I no longer take risks on behalf of Hoad.’ He stood up. ‘We must go at once. There is no need to pack anything for the boy. Hoad will provide adequately – even generously.’

‘Sir,’ protested Anna, angrily. ‘You took Heriot’s father for your wars, and he never came back, and now you’re taking Heriot. It’s not funny to us.’

‘My dear,’ said Lord Glass, speaking now in a very different voice. ‘I have a superficial nature that can’t gracefully abide some of the acts I am bound to perform. I joke about many things, including my own misfortunes. My father lost three sons in the King’s wars, and I have lost my eldest. But, like me, you have other boys coming on, and that’s why I am the King’s man, since, after all our wars, he is turned powerfully towards peace, and may well turn us all with him. His reign has brought many blessings, I think, and may bring more, no matter what you may feel at the moment.’

‘It’s true,’ Great-Great-Aunt Jen said with a sigh. ‘We’re bound to submit. Heriot’s our sacrifice this time round.’

‘And a piece of good advice from one who knows – keep your other boy away from Diamond. It seems more and more likely Heriot had a vision of a future possibility, so Diamond might not be altogether suitable for your Carron. Keep him at home or try some other city. Now, boy Heriot! We’ll sleep at my house tonight, and take you to the old battlefield tomorrow. Indeed they are hammering a primitive peace together out there, and I am expected to strike in myself on the part of the King,’ Lord Glass said. ‘Say your goodbyes rather quickly, my dear. And think of all this as an adventure – maybe the road to fortune.’

Heriot looked deep into those smoky eyes for a moment, then let his quivering shoulders relax, and gave a long sigh.

‘If I must, I must,’ he said submissively. ‘May I take my cards with me? They’re out in the courtyard.’ He held his breath.

‘The cards,’ Lord Glass looked at Great-Great-Aunt Jen rather than Anna. She looked doubtful.

‘It’s an ancient set,’ she said. ‘We wouldn’t get another like that. But all right. Be quick.’

Heriot smiled a little, turned and gave Lord Glass an appeasing glance.

‘That’s a good boy,’ said Lord Glass.

Heriot moved slowly to the door, expecting that, at any moment, someone would remember he had put the cards in his pocket, and he would be called back sternly.

However, as they began talking again behind him, he arrived safely in the kitchen.

‘Heriot …’ said Baba. ‘What’s happening? Are you to be taken?’

‘Tell us!’ cried Ashet. ‘Don’t keep us waiting. Is your fortune made?’

Nella, with her baby in her arms, smiled at him.

‘I’ll tell you in a moment,’ Heriot replied, amazed at his own easy, natural voice. ‘Look, I’m to get something for them … something from outside.’ He came to the door of the kitchen where Cloud was watching the little ones, still running in circles and jumping over the tiny stick. Cloud smiled.

Shuddering inside his clothes at the sight of an Assassin overlooking the babies, Heriot walked calmly past, offering no explanation or excuse, then out through the courtyard gates. And then, at last, he allowed himself to run, to run as fast as he could into the old barn. Once there he climbed a ladder into a loft, piled with loose hay. He burrowed into and through, letting it fall behind him. For a moment he thought he might stick there and smother, but finally he won through.

On the other side of the piled hay there was a very small window directly under the peak of the roof. Turning to face back the way he had come, he sat on the sill, reaching out and then up, until his desperate fingers, groping up across the outside stone, encountered a familiar hold, a channel made to drain rainwater into a stone cistern.

As Heriot began wriggling up out of the window, angling himself and holding his breath as he did so, he heard voices questioning, and feet beginning to pelt across the courtyard. As he pulled himself out on to the roof, feet began t

o shift the hay in the space below him. As he rolled down softly into the cleft between two ridges of stable roof he heard Lord Glass’s voice.

‘Cloud, I am to blame, I saw him put those cards into his pocket. But we’re wasting time. He will have made for the hills.’ The footsteps retreated.

Heriot had begun to breathe rather more easily when suddenly he heard Wish’s voice. ‘He’d be too big to get through that window, wouldn’t he?’

‘Right!’ said Radley from somewhere, and then added, ‘All this, it’s some sort of mistake.’

‘Get away with you!’ Wish answered. ‘He’s something really wild. I’ve always known it. We fling them up from time to time, don’t we? They’re like a throwback to the old people, the Gethin. Still he’s ours, not theirs. So we won’t look too closely. Come on now before they get suspicious.’

Then he set off walking rapidly … treading heavily … as if the sound of his boots might be sending some sort of message up into the space above him.

Heriot lay still, listening to the search going on below. When night came down around him stars pricked into life. Silence fell. Finally, in spite of the hard tiles and the cold, Heriot slept for a while, only to wake shivering, frowning, puzzling, and staring up into the night while the stars, wheeling above him, stared back without sympathy or even curiosity.

And at last … at long last … the first, faint transparency moved above the eastern horizon. Heriot had no choice. He must move on. Aching with cold, wet with night dews he slid to the edge of the dairy roof, arriving at a corner cut back into rising ground, where he crouched for a moment, trying to wring life back into his fingers before lowering himself over the edge of the roof. His cold hands, not yet properly restored, let go before he was ready. He had only a small distance to fall, but it was hard to judge distance in the dark, and the impact drove his knee into his stomach, so that he rolled on the ground, winded. A dog began to bark, but there was no response from the silent house. Picking himself up, limping to begin with but recovering as he jogged, then raced away, Heriot made for the hills.

Shock Forest and other magical stories

Shock Forest and other magical stories The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom

The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom Aliens In The Family

Aliens In The Family The Magician of Hoad

The Magician of Hoad Twenty-Four Hours

Twenty-Four Hours The Gargling Gorilla

The Gargling Gorilla Kaitangata Twitch

Kaitangata Twitch Heriot

Heriot The Changeover

The Changeover