- Home

- Margaret Mahy

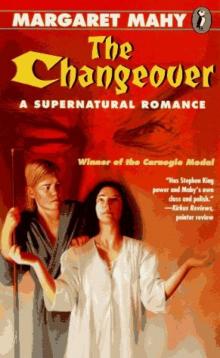

The Changeover

The Changeover Read online

The Changeover: a Supernatural Romance

by Margaret Mahy

1 Warnings

Although the label on the hair shampoo said Paris and had a picture of a beautiful girl with the Eiffel Tower behind her bare shoulder, it was forced to tell the truth in tiny print under the picture. Made in New Zealand, it said, Wisdom Laboratories, Paraparaumu.

Just for a moment Laura had had a dream of washing her hair and coming out from under the shower to find she was not only marvellously beautiful but also transported to Paris. However, there was no point in washing her hair if she were only going to be moved as far as Paraparaumu. Besides, she knew her hair would not dry in time for school, and she would spend half the morning with chilly ears. These were facts of everyday life, and being made in New Zealand was another. You couldn't really think your way into being another person with a different morning ahead of you, or shampoo yourself into a beautiful city full of artists drinking wine and eating pancakes cooked in brandy.

Outside in the kitchen the kettle screamed furiously, begging to be taken off the stove. Laura, startled, emerged from under the shower only to discover there was no towel on the rail. She could hear Kate, her mother, moving about in the room next door, putting the kettle out of its misery, and tried to shake herself dry as a dog does though she knew it could never work.

"There's no towel, Mum," she called fretfully, but as she spoke she saw a towel in a heap by the door and grabbed it eagerly. "It's all right! I've got one. Oh blast! It's damp."

"First one in gets the driest towel," Kate shouted back from the kitchen.

The mirror had been placed in the steamiest part of the bathroom and showed her a blurred ghost. However, its vagueness suited her, for she was uncertain about her reflection and often preferred it misty rather than distinct. No matter how hard she tried to take her face by surprise, she could never quite manage it, and found it hard to be sure what she looked like when she wasn't trying, but her body was easy to know about and filled her with a tentative optimism.

"You're beginning to look all right from a distance," her school friend Nicky had told her. "Only seeing you close up spoils it. You're too simple. Get your mother to let you have a really trendy hair cut, or a blond streak in the front or something."

Laura did not want a blond streak. Mostly she was happy being simple and living simply at home with her mother and her little brother Jacko. Yet sometimes, confronting the mirror, Nicky's remark came back like a compliment, suggesting that changes were now possible for her if ever she wanted them.

Out in the big room across the narrow hall it was Kate's turn to complain.

"I can't have driven home in just one," she was saying. "I'd have noticed everytime I changed gear."

"Lost shoe!" announced Jacko as Laura, the towel wrapped clammily around her, ran past him into her bedroom.

Once through the door she stopped. Just for a moment something had frightened her, though she had seen and heard absolutely nothing special. Yet, even as she stood there, she felt it again, like the vibration of a plucked string.

"I've looked absolutely everywhere," Kate said, a familiar note of morning panic creeping into her voice. Laura, shrugging away that inexplicable tremble in her blood, began to scramble into her school uniform— all regulation clothes except for the underpants, because it was a point of honour with all the girls at school never to wear school underpants. It was a stricter rule than any the school could invent.

"It's going to happen," said a voice.

"What's going to happen?" Laura asked before she realized that the voice had spoken inside her, not outside in the room.

It's a warning, Laura thought with a sinking heart. She had had them before, not often, but in such a way that she had never forgotten them. It always seemed to her afterwards that, once she had been warned, she should be able to do something to alter things, but the warning always turned out to be beyond her control. The warning was simply so that she could prepare to be strong about something.

"Still no shoe!" said Jacko, standing in the doorway to report progress.

Laura picked up her hair brush, looking into the mirror in her room, the best one in the house because the light from a window fell directly on to it. She stared at herself intently.

I don't look so childish, she thought, turning her attention from the warning, hoping it might give up and go away. But her reflection was treacherous. Looking at it, she became more than uneasy; she became frightened.

Sometimes small alterations are more alarming than big ones. If Laura had been asked how she knew this reflection was not hers she could not have pointed out any alien feature. The hair was hers, and the eyes were hers, hedged around with the sooty lashes of which she was particularly proud. However, for all that, the face was not her face for it knew something that she did not. It looked back at her from some mysterious place alive with fears and pleasures she could not entirely recognize. There was no doubt about it. The future was not only warning her, but enticing her as it did so.

"Stop it!" said Laura aloud, for she was frightened and when she was frightened she often grew fierce. She blinked and shook her head, and when she looked back, there she was as usual: woolly, brown hair, dark eyes, and olive skin, marked off from her blonde mother and brother because her genes were paying a random tribute to the Polynesian warrior among her eight great-great-grandfathers.

"Help!" she said, and bolted across the narrow hall into the room her mother shared with Jacko, which looked empty at first because Kate was on her hands and knees scrabbling under the bed, in case the shoe had hidden itself there during the night. "Mum!" she said. "No fooling! I've had a real warning."

"What do you mean?" Kate's irritated voice struggled up through the mattress.

"It's happened again," Laura said.

"I know it's happened again," Kate said, but she was talking about something different. "It's the second morning running. Just tell me how a perfectly ordinary — no, a nice, rather expensive — shoe can walk away overnight, and I'll give you a reward."

"I looked in the mirror and my reflection went older all of a sudden," Laura said.

"Wait until you're my age and that will happen every morning," Kate declared, her voice still muffled. "There's nothing here but dust."

Jacko stood in the doorway, holding his Ruggie and watching them as if they were doing a circus trick for his amusement.

"The world's gone funny," Laura complained. "It would be dangerous for me to go out today. I'm staying at home in a good, strong bed. Could you write a note?"

"Write a note on Thursday?" cried Kate coming out from under the bed, brushing dust from her palms. "You must be crazy, Laura! I need you much too much on Thursdays. It's late-night tonight, and who'd collect Jacko, take him home, give him his supper and read him a story? No notes on Thursdays and that's final."

"I can't choose the day," Laura said. Her voice was already giving in. "It chooses me."

"Thursday isn't allowed to choose you," said Kate firmly, as if she could control destiny simply by refusing to take any nonsense from it. "Be very careful, that's all! Look both ways! Keep out of sight of the teachers!"

"Oh Mum, it just isn't like that!" Laura protested. "It's a warning about something serious. You don't know what it's like."

"Tell me later," said Kate, but Laura knew she could not tell. It was a condition that could not be described. People had to have faith in her, and somehow this was asking too much of them, especially in the morning, when life ran in three different directions and only one of them was hers.

Kate was seized with a memory that became an inspiration and hobbled into the big room where she found her shoe on the mantelpiece. Standing by the empty fireplace last night she had absent

mindedly put her shoe there while she looked at a drawing of Jacko's — a happy, family drawing, for that was all he could draw. There they were — Laura, Jacko and Kate, wild yet geometrical, with huge heads and little legs and smiles so wide that they extended beyond their faces on to the paper around them. Under the influence of these smiles, Kate relaxed once more and began to walk evenly. Her shoe had come to heel and she forgave it at once.

But for Laura, who had come apart from the world, reconciliations were not easy. She looked at the soft sky. Only a few minutes before, it had been simple, clear and beautiful, but now she felt all summer leaning its weight against the house, breathing a hot and wolfish breath at her.

"Where's your basket, Jacko?" asked Kate and Jacko ran to get his basket which held a clean jersey, clean underpants, his library books, his special tiger book, and Rosebud, a pink, smiling crocodile made of felt. He carefully folded his Ruggie and put it on top of all these valuable possessions.

"Come on!" Kate said. "Let's get this show on the road, shall we? I do hope you're feeling strong, Lolly, because I have a feeling the car might be difficult to start this morning."

"Just for a change?" Laura asked, politely sarcastic because the car had been difficult to start for weeks without exception.

"It needs its battery recharged; probably needs a new one," Kate said. "They're so expensive." She gritted her teeth in financial agony. "Never mind, once we get going it will be all right. You keep an eye on Jacko, Lolly. Then I'll be sure where he is."

Laura admired Kate's heroic appearance as she leaned her weight against the car doorway, forcing it to inch forward. Even pushing a car she managed to look graceful and pretty, smiling fiercely to herself, her fair hair boiling around her head. The road sloped away, slightly at first and then more steeply. The trick was to get the car rolling, jump into it and shock-start it on the steep part, and this Kate did, as she had done many times before. Across the road, Laura's next-door friend, Sally, stood waiting for her father to come out of their family garage and drive her to a private school on the other side of town.

"We won't be living in this place all our lives," Sally had once said scornfully, but Laura liked the Garden- dale subdivision for she had just spent a wonderfully happy year there and was trying to lead the sort of life that would encourage a replay with interesting variations.

Sally waved again as, a little further down the slope, the car coughed and then settled to a steady, hoarse grumbling.

"There she goes, mate!" said Laura to Jacko. "Run, run as fast as you can — you can't catch me, I'm the gingerbread man."

"Gingerbread running, eaten by fox," said Jacko and seized his Ruggie to comfort himself in case a fox came by.

"I wish I had a Ruggie," Laura said. "I need one more than you do right at this moment."

They hastened to catch up with Kate, piling in, brother, sister, basket, pink crocodile, school pack and all. The car shuddered with welcome.

"Don't worry!" Kate said to Laura. "I've done it so many times before."

"Not on a day with warnings!" Laura said. "Just for a moment I thought you might fall under the wheels and get mashed up."

"You and your warnings!" Kate said affectionately, but almost as if she were speaking to Jacko instead of Laura, who was fourteen and deserved a different voice.

"All right! Don't believe!" said Laura. "I don't really blame you, but it's true, that's all. Everything lights up as if I were playing Space Invaders and says, Warning! Warning! Warning!"

"Have you been into that place again?" Kate said, gladly talking about something else, real without superstition. "I wish you'd keep clear of it. There are a lot of rough types there and I don't want you getting into any trouble you can't handle."

She was talking of the Gardendale Video Parlour where the Space Invaders machines peeped and sang all day. It was always alive with young men who couldn't get work and had to kill time, as well as children playing truant from school.

"Warning!" insisted Laura refusing to be diverted. "First the look of everything changes ... things stop flowing into each other and stand separate, a bit silly- looking but scary. The world gets all accidental. It's as if you had a house which seemed to stay up by being propped against itself and suddenly you realized nothing was really touching after all." She slowed her voice down. "The weekend Dad left with his girlfriend I had warnings. That's why I didn't get more upset. You said I was very brave but actually I was frightened it might be worse. I thought one of you was going to be killed or something."

"Julia's his wife now, not his girlfriend," said Kate, fastening on the least important thing. "You might as well learn to use her name. They're happier together than we ever were." But Kate meant that he was happier than he had been with her; he had always been very happy with Laura who looked like him.

Laura did not let herself be distracted by tired, sad, family recollections.

"And the next time it happened, that is in the last few years," she went on, "was when Sorry Carlisle came to school."

"Sorensen Carlisle!" Kate said and gave a little yelp of laughter. She sounded knowing and amused. "What on earth is there about that boy that you need to be warned about? It's like being warned about Red Riding Hood instead of the wolf ... Isn't he the school's model boy— clean, quiet, hardworking, going around with an expensive camera photographing birds — the feathered kind, of course. A bit dull, really!"

Kate was being unfair but she was not to blame. She had only Laura's descriptions to go on.

Sorensen Carlisle had appeared at Gardendale Secondary School eighteen months ago, although his mother had lived there since she was a little girl. She had a place in local history; had belonged there before the name Gardendale had appeared on the city maps, before the city had stretched and flowed between the spurs thrust out from the main range of hills to form this sudden suburb, an instant village within the city's wider boundaries. Friends who had known the family for years said Miryam Carlisle had never been married, and she did not explain Sorensen in any way except to say that he was her son, sixteen years old, apparently studious, and marked out by a terrible stammer which had, however, grown steadily better over the last year and a half and was now barely noticeable. He had done all the average school things, played cricket in the summer, and rugby in the winter, and won a special prize for photographs of estuary birds in the Secondary School Science Fair, winning a book about birds of New Zealand for the school library. In class he did well, but not so well that he bothered himself or others. His unfortunate characteristic from the point of view of teachers was that he couldn't resist a smart answer, but this did not worry Laura who had never exchanged more than half a dozen words with him. On these occasions he had spoken in a soft, hesitant voice, simply a prefect instructing a younger pupil. What was impossible to describe was the remarkable smile accompanying his instruction— a smile directed at her alone. Laura had never mentioned this smile to Kate or the reason for it.

Even now she hesitated, and as she did so Kate was moved to say, "If you're never warned against anything more threatening than Sorensen Carlisle you've got nothing to worry about."

Outside, Kingsford Drive unreeled as long and straight as the surveyor's string that had laid it down only a few years earlier. However, road repairers were already struggling with something subterranean, and Laura, Kate and Jacko progressed crookedly, driving between giant pre-historic monsters, earth-moving machines making an island of Silurian time in the twentieth-century streets. The Gardendale subdivision reeled past and though all the houses were not exactly similar they were at least cousins, or maybe members of the same team. Laura and Kate were coming close to the gates of the Gardendale Secondary School and the footpaths began to teem with school uniforms all moving in the same direction. Taller than almost anything else in this flattened-out area of a flat city, the Gardendale Shopping Complex reared up ahead, a cross between the Giant Supermarket from Outer Space and an Industries Fair, for it had been designed to l

ook jolly, and succeeded in its own way. Kiwi Car Sales, said a confident sign, and the salesman was already out whisking the night's dust from mudguards closest to the ground. Laura knew a lot of people despised the Gardendale subdivision, but she had grown fond of it and sometimes loved it for the very things that other people criticized it for — because it was new and raw and rough and filled with vandals who wrote strange things on walls with spray cans of paint. At night its streets became dangerous, but she frequently enjoyed this razor-edge of risk waiting outside their comfortable, family door. Laura thought about all these things in a single second while she prepared to tell her mother something she had known for a long time, but had never told anyone else before.

"Sorry Carlisle is a witch!" she said. "No one knows but me."

Kate did not laugh or tell her not to be silly. She knew when things were serious even when she was driving around a fairy ring of oildrums standing in the middle of the road.

"Lolly, if you'd thought all day I don't know if you could have come up with an unlikelier witch than poor Sorry Carlisle," she said at last. "He's the wrong sex for one thing, which in these non-sexist days shouldn't matter much, but from what I can make out he's about the best-behaved boy in the school. You're always complaining about him because of it, and you can't have it both ways. Now," said Kate, starting to sound really enthusiastic, "if you'd mentioned his grandmother, Winter, or even his mother. Quite a different story — witches to a man — a woman that is ... They've got the sort of craziness that gives them class!" Kate added. "Mind you," she went on before Laura could say anything, "I can't imagine them bringing up a boy of seventeen or eighteen between them. Old Winter gets madder day by day and Miryam floats around staring into space as if she saw only tomorrow or the next day. But the boy seems as normal as the rest of you... with a slight edge towards good behaviour, perhaps."

"Have you finished?" asked Laura. "Listen — I know all about Sorry Carlisle! No one notices but me. Mum, can't you see he's like a TV advertisement — matched up with an idea people have in their minds, not with real life. Even when he does something wrong you can feel him ticking it off on a sort of desk diary — '20 November — Please Note — think of something wrong to do!' And no one notices except me. He knows I notice, mind you!"

Shock Forest and other magical stories

Shock Forest and other magical stories The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom

The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom Aliens In The Family

Aliens In The Family The Magician of Hoad

The Magician of Hoad Twenty-Four Hours

Twenty-Four Hours The Gargling Gorilla

The Gargling Gorilla Kaitangata Twitch

Kaitangata Twitch Heriot

Heriot The Changeover

The Changeover