- Home

- Margaret Mahy

Kaitangata Twitch Page 4

Kaitangata Twitch Read online

Page 4

‘He wasn’t!’ Kate said, turning on Rufus impatiently. ‘He’ll find a way to make money by ruining it. That’s what he was telling us. And he was really nasty. It wasn’t so much what he said, as the way he said it.’

‘Yeah, well,’ said Lee Kaa. ‘He just might be taking on a bit too much if he tried his development tricks on Kaitangata.’

Meredith was still thinking of the name ‘Shelly Gentry’. The Kaitangata beach mightn’t be called Shelly Beach just because of its shells.

‘Who was Shelly Gentry?’ she asked.

‘Don’t they bother to teach you history these days?’ said Lee. He jerked his thumb back towards Kaitangata. ‘A kid drowned. Well, probably drowned! Vanished, anyway. Vanished out on Kaitangata.’

‘What happened to her?’ Rufus asked.

‘I told you!’ said Lee. ‘Disappeared on her birthday. There was a party over there on Shelly Beach. Kids everywhere having a good time. Then there was an earthquake, they say. And we had an earthquake ourselves the other day,’ he went on, flicking the conversation out of the past and into the present as if it were all part of the same thing. ‘The old Kaitangata twitch! First the twitch, and then the trouble!’

‘Who says that?’ asked Rufus.

‘People!’ said Lee vaguely, answering Rufus but looking at Meredith again.

‘Coming up for a cup of tea?’ Kate interrupted.

‘Might call in on my way back,’ said Lee. ‘Tell your dad not to worry too much about Sebastian.’

‘We have to worry,’ cried Kate hotly. ‘He’s a councillor now, isn’t he, and a lot of other councillors are licking his boots, so he’ll probably be able to grant himself permission to develop anything he wants to develop. And he wants to hurt us . . . our family. I could tell he does just from the way he looked at me . . . at us, that is. And also, he doesn’t care what he does. I mean, look at the Creek across there, screaming every weekend with speedboats and jet-skis.’

Lee made a sound, half-snort, half-laugh.

‘Katie, I’m on your side,’ he said, ‘but I remember a lot of things you don’t. I remember how we old-timers had to get used to you lot,’ he said.

The Gallaghers had been about to move off up the Zigzag, but now Kate stopped, looking sharply at him. ‘How did we change things?’ she demanded.

‘Roads!’ Lee said. ‘Roads came after you lot, like tame snakes. Then, of course, everyone else followed the roads: cars, motorbikes, the lot.’

‘Well, roads . . .’ began Kate, suddenly confused. ‘We have to have roads.’ And then she fell silent, frowning as if Lee had asked her a riddle.

‘We could do without. We could ride over the hills on our donkeys,’ cried Rufus, gleefully, sensing Kate’s uncertainty. ‘You could leave for school the night before and then get back—’

‘Shut up!’ said Kate. ‘Anyhow, it’s not the same. Donkeys are part of Nature.’

‘See you on my way home, maybe,’ said Lee, grinning.

Kate’s face cleared. She grinned back.

‘I don’t care,’ she said. ‘We have to be miles better than dirty old Sebastian Cardwell.’

‘I’m with you there,’ Lee said. ‘And I’d put my money on Kaitangata . . . if I was a betting man, that is.’

He winked, then walked off down the beach. Meredith, Rufus and Kate set off up the hill all thinking of breakfast. As they came out at the top of the Zigzag their father suddenly appeared on the verandah, leaped down the steps, (automatically avoiding the third one, the wobbly one), and onto the lawn in front of them. He flung out his arms and whirled around, as if he were Rufus, his red hair standing out almost like a wig.

‘We were beginning to worry that you might be gone for good,’ he cried. ‘Your mother’s been at me, telling me what a pain I’ve been with my moaning and groaning, so I’ve promised to reform and from now on it’ll be all feasting and fun.’

And then, to prove it, he began to dance and sing.

‘I’ve just come back from a cannibal isle

Called Hi-tiddly-hi-ti-ti Isle!

Tum tum tum tum . . .

‘I forget the next bit . . . Oh yes.’ He slicked his hand back over his head as he remembered a bit of the song he had lost.

‘On Hi-tiddly-hi-ti Island,

Everybody wears a smile.

On Hi-tiddly-hi-ti Island,

Everybody lives in style . . .’

And then, because he had forgotten the words again, he sang ‘Tra la la’, jigging happily at the Edge of the World while behind him, on the verandah, Rufus joined in, dancing, as it happened, rather better than his father.

At the sound of this old, cheerful song, Meredith felt all strangeness and threat flow out of the day, and fun flow back into it. When ten minutes later she stole a passing, almost accidental glance at Kaitangata through her bedroom window, it looked altogether ordinary, just a lump of land with shallow water around it. Which was what it was, no doubt about it.

9

Flick!

Meredith scrambled out of the blue canoe and stood on the Kaitangata beach, looking up over the gorse to the clenched fist of the island. Once again she was bathed in that puzzling light and supposed, within her dream, that she might be dreaming.

‘You again!’ she said aloud. ‘What do you want?’

‘Eat! Eat! Eat!’

‘Eat what?’ Her voice seemed to run ahead of her down the beach, slipping over the seaweed and driftwood as if it expected her to follow it. ‘Oh no!’ she said. ‘I’m not going there again. It was me you tried to eat last time.’

Flick!

‘Hungry!’

And then she began to wake up, to find herself lying out on the verandah in the early summer morning.

By now Meredith felt she was becoming used to that voice. She looked around, wondering if she might even become used to waking up in some place other than her own bed. Certain dreams seemed to have the power to nudge her out into the world. She pulled herself onto all fours, feeling rather bruised after sleeping hard. She stretched upwards: she stretched sideways. Then she went inside to make herself an illegal pre-breakfast breakfast of noodles. She would take it up to her room, read as she ate it in bed and then come down later to wholesome stewed apple, organic muesli and home-made yoghurt. She felt she deserved comfort. And it was a Saturday morning, after all. No school. Bliss!

The phone in the sitting room rang sharply. The day woke up. Perhaps it had been having a dream of its own. Meredith could hear her father grumbling sleepily as he padded down the passage to answer it.

‘Who?’ she heard him say. ‘What?’ There was silence while he listened. Then he began shouting again. ‘I knew it! Didn’t I tell you? Yes! No! I’ll contact our local group! We’ll have to organise – call a meeting, work out submissions. A protest – yes! Thanks for the info! No! Not too early! Never too early! Never too late! Bye for now!’

He slammed the phone down.

‘What’s wrong?’ asked Meredith’s mother. Her voice was both sleepy and worried at the same time.

‘It’s war,’ he cried. ‘Didn’t I say . . . Haven’t I been telling everyone—’

‘Go on! Just tell me again,’ Mrs Gallagher said, sounding wide awake now. ‘Then we’ll put on our tin helmets, bring the donkeys inside and dig up the front lawn.’

Meredith could hear her father take a deep breath.

‘I told you I should have gone to that meeting last night,’ he declared. ‘That was Stafford Keys on the phone. The council produced that new District Scheme at last – sprang it on everyone – and under this scheme the entire Beckett block and all Wittwood land will be reclassified as “residential”. Cardwell must have had this all cooked up beforehand. Stafford says it’s a really comprehensive document, not the sort of thing anyone slings together overnight. He says it would have taken months to come up with something like that. He was obviously working on it even before he was elected to the council.’

In the kitchen Meredith was dropping noodles into

a saucepan of boiling water.

‘Dad,’ she heard Kate saying, ‘what’s wrong?’

‘I’ll make us all a cup of tea,’ said Mrs Gallagher. ‘No use trying to sleep in this morning. Why on earth did Stafford ring so early? Later on would have done just as well. Couldn’t wait to pass on a bit of bad news.’

Coming into the kitchen she jumped at the sight of Meredith, then looked at the saucepan on the stove. ‘What on earth are you doing?’

‘I had a dream,’ said Meredith. ‘I woke up.’

‘Woke needing instant noodles. Couldn’t you wait for a proper breakfast?’

‘I didn’t know everyone else would wake up early, too,’ Meredith said, trying to hear what her father and Kate were saying as they exclaimed and shouted in a broken chorus of despair.

Their voices were still bouncing backwards and forwards when she came out into the sitting room, her bowl of noodles against her chest and prepared to listen in.

‘Right on, Dad!’ Kate was saying, thumping her father on the shoulder. ‘He won’t know what hit him when we get going. He’ll race back overseas. It’ll be a lot safer for him in Sydney.’

‘It’s not really so safe for him these days,’ said Meredith’s mother. ‘Apparently there’s a big group, a conglomerate that’s moving in on him. “Eyot Undertakings”, according to Judith Appleton. Something like that, anyway.’

‘Undertakers are people who arrange funerals,’ said Rufus. ‘Idiot Undertakings!’

‘Eyot! It’s the name of the man who runs it, Harvey Eyot, and as well as that it’s a word for a small island – at least I think it is,’ said Mrs Gallagher uncertainly.

Flick!

Meredith quickly looked towards the window.

Outside, the morning light had grown stronger and brighter. That fist of rock rose out of the sea, encircled by an amulet of mottled gold. Above the gorse she could see streaks of scarlet thrift. It suddenly looked as if, there below the fist, crimson were trickling down into a yellow cuff. Kaitangata was bleeding, or perhaps, thought Meredith wildly, the blood that seemed to be trickling from between the rocky knuckles was being squeezed from a lost child, secretly crushed for fifty years by the island’s clenching fingers. It was as if her father’s angry cries had shocked the island into that other, older life that only she seemed to know about. But then she knew, as no one else did, that Kaitangata was never as restful as it pretended to be. It was always listening in.

10

‘You know what?’ Rufus said to Meredith, as they walked from the school bus stop down the road that led between their donkey paddock and the Cardwell boatshed. ‘Allan Ponty says his father’s on Sebastian Cardwell’s side.’ Rufus spoke quietly for someone who was usually a shouter. He sounded puzzled and a little subdued.

But Meredith was not surprised . . . not by then. You could easily tell what the various families thought about the new District Scheme by listening to what the kids at school had to say. The Pontys, whose orchard was on the western side of the Gallaghers’ land, and the Shepherds and the Appletons, further along towards the head of the bay, were all excited and hopeful of subdividing their land into house sections, then selling it for a lot more money than they had paid for it in the first place. It was tempting to believe they would become suddenly rich. And both the Shepherds and the Appletons, families who had lived in the bay for longer than the Gallaghers, seemed to be saying that they were the true people of the bay and had the most right to say what was needed, just as Mr Gallagher felt that he and his family had more right to be there than anyone who might have come after them.

‘It’s easy for your dad to yak on about the environment,’ said Oliver Shepherd. ‘He’s only got two hectares and a few donkeys. But suppose he could cash in big himself – well, he wouldn’t be such a raving greenie then, would he?’

‘You’ve got to be realistic,’ said Sharon Ponty. Sharon and Meredith spent a lot of time together but they were not altogether best friends, for Sharon was a year older than Meredith, and bossy with it. Suddenly she was laying down the law about the bay and Sebastian Cardwell’s possible plans for it. ‘We’re too close to the city to escape development – and the land’s not all that great for farming anyway. I mean, it’s been a real struggle after last year’s drought. No let-up!’

‘You’re just saying that because you’ve heard grownups saying it,’ Meredith replied. She knew this was true, because of the way Sharon came out with the word ‘realistic’. Anyone could hear the echo of some confident adult voice underlying Sharon’s.

‘And you’re just jealous,’ Sharon replied, sounding much more like her usual self this time. Soon after this Allan and Sharon stopped hanging out at the Gallaghers’ after school.

For a week or two the proposed District Scheme hovered above the Gallagher family, like a dark angel, wings spread, whispering curses. The fringe of grass at the End of the World, the hills before and behind them – all things which had once felt as if they would last for ever – suddenly seemed frail and easily destroyed, though Mr Gallagher certainly tried to protect that old life. There were meetings of other anxious families in the Gallagher sitting room, and the new District Scheme, a block of ring-bound pages with an elegant photograph of the bay on the cover, went from hand to hand. It was studied, photocopied and scrawled on, and had notes, crosses and fierce exclamation marks drawn in its margins. Beside the till in the local store a petition appeared. We the undersigned . . . it began, and went on to talk about preserving the unique rural character of the bay communities. Every time they stopped off for milk and cat-food, or anything that Mrs Gallagher had forgotten to buy at the city supermarket, Meredith and Rufus would check who had signed the petition. Their own family name stood boldly at the top – first their father’s name and then their mother’s. Kate, Meredith and Rufus had not been allowed to sign because they were not ratepayers. Mr Gallagher had pressed his pen so hard on the paper that the ghost of his signature showed up on the pages below, hovering angrily over every other entry. No Ponty names appeared on the petition, and there were no Appletons or Shepherds. ‘Only one councillor has signed,’ said Mr Gallagher gloomily, which proved that he studied the petition too, when he thought his children were not watching. He began saying, ‘People will be sorry . . . but it’ll be too late by then.’

Yet within a month the threat had become somehow ordinary – part of everything else, like the season or the weather. Mr Gallagher’s first fierce horror was somehow soaked up by meetings, by letters to newspapers, by drafting protests and submissions and talk of a local referendum. As Christmas approached, the gossip about contacting the Department of Conservation and lobbying for the whole bay to be designated as a coastal reserve died away. Plans about holidays and swimming and family get-togethers took over.

11

It was late in the day but still light. Stealing away from family debate, Meredith felt certain that this was a time when Lee Kaa would have finished his gardening and that he too would be stealing time from everyday life, to sit on the log on the foreshore and play his saxophone. Sure enough, she could hear the mellow sound as she came towards the little spike of rock that separated one stretch of the beach from the next. The music seemed to reach out to meet her, to wrap itself around her like a melodious snake that danced her onwards.

‘Well, how are things going in the Gallagher world?’ Lee asked her. ‘Exciting times?’

‘Pretty exciting,’ said Meredith. ‘Mostly Dad and Kate shouting, and Rufus trying to egg them on, and Mum trying to quieten them down.’

‘I can imagine,’ said Lee.

‘It’s not that Mum isn’t on Dad’s side,’ Meredith hastened to say. ‘She’s just somehow more . . . more . . .’ She hesitated.

‘More resigned,’ suggested Lee. Meredith frowned.

‘Are you resigned?’ she asked.

‘Ah, there’s a question!’ Lee replied. ‘See, I’ve fought my own wars . . . won a few, lost a few. I did sign your dad’s petitio

n, though. Anyhow, now let’s play.’ He played a few notes himself before handing the sax over to her. He listened as she began, wavering a little at first, then settling into the sound and the song. The air darkened around them and it almost seemed as if the sound of the saxophone darkened too.

‘Now!’ said Lee, standing up. ‘Off you go or your brother will come dancing along, looking for you.’

Meredith stood up too. The family were used to her wandering off on her own, but it was true that they would come calling for her if it got really dark and she wasn’t home.

‘Might not see you again until after Christmas,’ Lee said. Suddenly he sounded shy. ‘Hey! I’ve got a present for you.’ He reached down behind the log and came up with a shoebox holding a huge shell – a great spiral spinning to a point.

‘Listen!’ said Lee. He put his lips against the pointed end and blew. A curious sound came out of it – not the pure and golden note of the saxophone but a sound that seemed to struggle into the world through sand and moss.

Flick!

Meredith saw Lee’s head turn as she found her own head turning, to look across the twilit harbour to Kaitangata, a black shape against the sky.

‘No use looking that-a-way,’ said Lee. ‘Watch this!’

He blew again, holding the shell in his right hand and flapping his left hand over the wide mouth of the shell. The sound rose, then sank away. It came towards her and then retreated.

Lee stopped blowing.

‘See what I’ve done?’ he said. ‘I’ve cut the tip off the shell and fitted a little mouthpiece onto it. It’s not like the sax . . . but one thing links into another.’

‘Flute to sax and sax to shell,’ said Meredith. ‘Can you play any sort of tune on it?’

‘You can get a bit of rhythm out of it,’ Lee replied. ‘And there’s always the sound, coming and going. Yeah! That sound might be enough.’ Then, very deliberately, he looked past her. Meredith turned. The beach was empty. ‘Plays a sort of lullaby, perhaps,’ Lee said. ‘It’s hard to get some babies to sleep.’

Shock Forest and other magical stories

Shock Forest and other magical stories The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom

The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom Aliens In The Family

Aliens In The Family The Magician of Hoad

The Magician of Hoad Twenty-Four Hours

Twenty-Four Hours The Gargling Gorilla

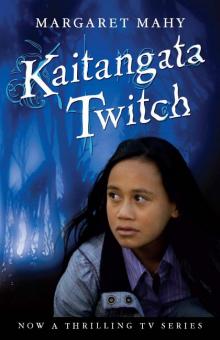

The Gargling Gorilla Kaitangata Twitch

Kaitangata Twitch Heriot

Heriot The Changeover

The Changeover