- Home

- Margaret Mahy

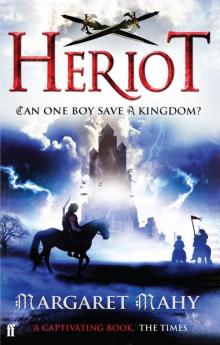

Heriot Page 18

Heriot Read online

Page 18

‘I would always have fought for you if I’d known you were going to be fighting beside me,’ Linnet declared.

She meant it. She meant it.

They walked down the winding stair towards a guttering torch, paling in that first morning light, and then out under an arched doorway on to the battlements. Far below them the Bramber flowed; far beyond them the three Rings of the city stretched towards the first rising hills of County Glass. Nothing in that outer world had changed, yet Linnet had never felt as consciously free as she felt now, as easy, as pure within herself. The Hero’s tower still blazed with light, but, as morning advanced, as edges and curves began to shine, and hints of depth and distance crept back into the world, these lights, too, were losing their power. The sound of voices singing came towards them intermittently. High in the Tower of the Lion, the King’s window shone faintly. Perhaps the sleepless King of Hoad was celebrating his son’s strange wedding with yet another night of careful work.

Watching the morning, and strolling along the battlements beside Linnet, Dysart felt he was made of paper and ink, made out of stories, and not all of them his own. Stories never sleep, he thought. They tell themselves over and over again. Beneath him, in the tunnelled walls, the campaigners were changing the guard. Celebration fires still smoked in distant city squares. They walked in silence, and the dissolving midnight beast, which had consumed Dysart when he was a dreaming child, grew hazy and doubtful. Inwardly he laughed at it, and drove it away.

At last they paused and leaned together in one of the embrasures, looking out into the King’s garden. Neither of them thought of the Magician, who had declared himself a monster and shut himself in the cage.

There was a step behind them. They turned together, looking away from the garden and the sea into the more resolute light staining the sky beyond Hoad’s Pleasure.

Betony was standing behind them, holding a glass and a bottle of wine in his pale hands, his face more naked than Linnet had ever seen it. His expression altered at once, as it always did when anyone looked into his eyes. Nevertheless Linnet had fleetingly glimpsed something in Betony – a terrible injury, old and mortal – before he had the chance to conceal it once more.

‘I see you have been celebrating my wedding,’ Betony said. He stared at them. ‘Rather too well!’ he added.

‘Someone has to,’ Dysart said.

Betony sighed, took his place beside them, facing the morning, and turning his back on the bulk of the sprawling city. ‘Oh, I’ve celebrated in my own way,’ he said. ‘I was able to talk to her – my wife, that is. We can’t stand the thought of each other. We’ve agreed not to contaminate ourselves. And we do understand each other … we’ve even become friends of a sort. Willing conspirators, anyway! My father can whistle and wait for the miraculous child, heir to both kingdoms. It just won’t happen. I don’t mind taking life out of the world, but I’ll never feed it back in. I may be cruel, but I’m not as cruel as all that.’

He looked sideways at them. ‘You seem to have celebrated my wedding in a particularly personal way,’ he went on.

Without turning, Linnet could tell he was smiling.

‘Linnet and I have promised to marry each other!’ Dysart said abruptly, anxious to hear what the idea sounded like in the outside world. Once spoken, it became both more and less than a private ecstasy … it became a policy.

‘Oh, of course you have,’ said Betony. ‘And I do think you should!’

Dysart and Linnet both looked at him suspiciously.

‘You might even get away with it,’ he said, smiling his wincing smile at their doubt, ‘now that Carlyon’s shown a little of his hand … well, of his heart, really! Have you told your father?’ he asked, turning to look at Linnet. ‘Or have you had other things on your mind?’

‘The King didn’t seem to be worried by anything Carlyon had to say,’ Linnet answered casually. She hadn’t given Carlyon or his visions of death and decay a thought.

‘Oh, don’t be naive,’ replied Betony scornfully. ‘Our father has never trusted Carlyon as Hero … he’s always wanted to hold Luce in reserve. Otherwise Luce would have been married, probably to you, well before this. And he’ll never forgive Carlyon for that trick last night, for turning Izachel loose at my wonderful wedding feast. So someday he just might give Luce the chance to do what Luce already longs to do. To do more than admire Carlyon … to kill him and become him. A sort of devouring! That cuts out marriage for Luce. And the Master wouldn’t mind you marrying Dysart, would he, if Dysart was a second eligible son, rather than a third.’ He shook his head. ‘It’s almost too neat a chance. Don’t trust it.’ He sounded neither sympathetic nor hostile … simply curious in a slightly drunken and weary fashion. ‘Or perhaps you’ll live happily ever after,’ he went on, smiling gently, ‘in Hagen.’ It was hard to understand how a voice so empty of expression could, nevertheless, express profound derision.

‘I could learn to do that,’ Dysart said defiantly, but as he spoke his thought twisted in his head. ‘If I could have Linnet and Diamond too …’

We could live in Hagen, Linnet thought like Betony’s echo, then pushed the thought away. Dysart must never know how quickly she had imagined him among mountains and forests of her home, how she had already stood him on the edge of a plateau from which one could look out over the whole land of Hoad.

‘Because,’ Betony went on serenely, ‘since I’m forced to be King, I must warn you I plan to be King, childless or not. Actually I can hardly wait. So no secret hopes of something beyond Hagen. I shall become King out of spite.’ The gentle flow of his voice suddenly sounded particularly sinister.

‘Besides, Dysart, you’d never be a true King. You’d be like our father. You’d try to do good: you’d try to be kind: you’d try to be human, and that would bleed the sense out of our sort of kingship. And, over and above any question of your inadequacy, I do so want my father to have the fulfilment of seeing me become what he’s forced me to become.’

‘You want to be King out of revenge!’ exclaimed Dysart.

‘It’s a good reason,’ said Betony mildly. ‘I’ll be different from my father in essence, because I’ll never be taken in by my own story.’

Glancing back at him, Linnet suddenly caught a vagrant reflection of light from a wet streak on his cheek. Betony was weeping. As she watched he touched the tear away with his right forefinger.

‘Rare wine!’ he said, looking at her. Then he licked his finger tip.

‘Talgesi’s not dead,’ Dysart pointed out. ‘Just gone away.’

Linnet leaned more deeply into the embrasure, staring down into the garden. Far below she could now make out an archery lawn, which she knew well. Something flashed out from the trees, a wheel spinning across the grass and chamomile. A strange child was cartwheeling through the King’s retreat, seeming barely to touch the ground. Betony and Dysart, backs to the garden, didn’t notice the somersaulting figure.

‘I really loved my father when I was very small,’ Betony said, still holding the glass high in the air, narrowing his eyes as he looked at the world through it. ‘I have no depth, as you know. I’m fascinated by surfaces and back in the beginning his surface seemed so wonderful, I thought he must glitter all the way through. And then, as I got older, I began to think there might be blackness, a perpetual bitter howling, and that was fascinating too … Since he didn’t love me I thought perhaps he hated me, and I enjoyed the drama of being hated. But when I realised he was nothing but a grey, dull struggler, who’d given up his own life for an inferior one – a royal donkey with a capacity for taking detailed care of things – when I realised I’d been born to be nothing more than a marker in his dreary labour, then I knew I’d never forgive him.’

‘From what I can make out,’ Dysart was saying cautiously, ‘people have been happier since he’s been King.’

‘But I’m not happier,’ Betony said. ‘I was born with a longing for extremity, and none of this is anything like enough. The crown, the

ritual, the castle … all nothing but tinsel!’

‘Well, perhaps you can’t be happy,’ Dysart suggested, rather brutally. ‘Maybe that’s one gift you don’t have.’

Down in the garden a second figure was strolling on to the archery lawn. Heriot, whose last words to her had been a promise that he would never leave his cage, was walking between the trees. Linnet stared down at him, frowning and transfixed, while Betony watched Dysart with a suddenly inimical stare.

‘You are completely wrong!’ he said. ‘I know about happiness. I can feel happiness beating off you this very moment, and how do I recognise it? Because I have been happy, on rare occasions. I want happiness very badly.’

But Linnet, watching Heriot Tarbas, and wondering what on earth could have brought the Magician out of the cage, wasn’t thinking of Betony’s happiness. Something had happened to change the Magician’s mind. And, even from this distance, calling on sharp memory rather than sharp sight, she now recognised the cartwheeling boy as the one who often followed him. Strange rumours circulated about them, but Lord Glass had never tried to cut the boy out of Heriot’s life. Had Heriot reached out from his cage and opened its door for him? She looked at Dysart, who was leaning against the wall beside his brother. As if her gaze were a touch, he now turned his odd-coloured eyes towards her, turned and then, together, they looked out over Diamond.

‘Funny!’ said Dysart ‘I’ve never felt so close to it before.’ He didn’t say what he was talking about but Linnet knew. ‘It’s as if giving it all away has mixed me into it more than ever.’

Betony understood. ‘You’ll never give Diamond away. Linnet, be warned! He’ll break every other promise, but that one.’

Dysart treated Betony as if he were a whisper as impersonal, as errant and senseless as wind or rain. He simply laughed, and shook his head. Though he answered Betony it was Linnet he was really talking to.

‘You’re only jealous,’ he told Betony, before saying what was real to him at that moment. ‘Anyway I’m a Magician in my own way. I’ll fold Diamond up and carry it always, tucked into a little press in my head. Then, whenever I need to, I’ll take it out … shake it free … I’ll have it all.’

And, as Dysart spoke, Linnet believed he really might be able to contain the whole city: that the castle at its heart, the river like a flowing question mark, the three Rings, the merchants, markets, magicians, mottoes, libraries, laundries, lines of washing, the jewellers, the poems on walls, and the gongfermors carrying buckets of excrement to dump in the poorer part of town, even the King and the Hero, would all be Dysart’s for ever. He might even be able to share it with her, if ever she wanted it. And suddenly it seemed as if all the shifting entities of the city had really been standing still, and it had always been Linnet, the heiress of Hagen, and Dysart, the third son, who had moved and changed, dancing between all the confusing others.

‘Dice heart!’ Dysart said suddenly, but whether he said it to Linnet or Betony or to the morning no one could tell. ‘No one will ever be able to take it away from me. I’ll gamble on that.’

He took Linnet by the hand, without noticing the Magician in the garden below, and turned her to face the east and the confidently rising sun.

Part Four

Gone

27

Challenging the Hero

‘Time!’ said Heriot. ‘It doesn’t give up, does it?’

‘One moment little, the next big,’ said Cayley in his husky damaged voice. ‘Me that is, not you. You’ve always been big.’

‘Neither of us has ever been as big as we are now,’ Heriot said. ‘Are you off to fight somewhere? Fight! Fight! Fight! That’s all you think of.’

‘I’m working out with Voicey Landis,’ Cayley said. ‘I’m his favourite and it’s not just being big and strong. I’m – what’s that word? I’m agile. That means quick,’ he added, proud of a new word. ‘The ones that are even stronger than me, they dive in to strike me. Down comes the sword but – hey – I’m already over there, and spinning in from the side.’ He mimed a graceful movement. ‘I’m strong enough, but quickness, that’s my skill. And I work at it more than most.’

‘I know,’ said Heriot. ‘When I ask you to tidy our shed you always say you’ve got to practise.’

‘Oh, that!’ said Cayley. ‘Well, you don’t tidy. You just crouch by the King, telling him who means well and who doesn’t.’

‘That’s my work,’ Heriot said. ‘That, and spreading a bit of fantasy around when the King has noble guests.’ But as he spoke his expression became remote. Over and over again, with every new day, the old questions still worked through him. The world around him seemed to thrill with intention, but he somehow knew he wasn’t being what he was intended to be.

‘Do you tell him about Betony Hoad?’ asked Cayley.

‘I don’t have to,’ Heriot said. ‘Anyone can read the Prince. The King can. Lord Glass can. Betony Hoad wants to be marvellous beyond anyone else – even when he’s King it won’t be enough for him. He’d like to be a Magician too, but being a Magician is something you’re born to, like me.’ He sighed. ‘Be noble! Be strong! Whatever! Being a Magician isn’t something you can win.’

‘Then off you go, and get on with the work you were born to, and I’ll get to mine,’ said Cayley. ‘If I don’t see you tomorrow I’ll see you the next day.’

Heriot walked through the orchard, across one echoing courtyard, then another, up a short flight of stairs, choosing to enter the castle through its kitchens where the cooks and butlers, the butchers, cleaners and other people who lavished care and attention on the halls and chambers of the castle, greeted him with a certain caution, but with friendship too. He was the Magician of Hoad, but he understood their work. There had even been occasions when he had joined them, scrubbing platters and benches, listening to the castle gossip and gossiping in return. Moments like this gave him a homely feeling. But today he simply grinned and waved and walked on, climbed other, grander stairs and came into a lobby whose stone walls were softened by tapestries. Suddenly he found himself confronted by Dysart.

‘You’re late,’ said Dysart. ‘The Lords of the Islands are here already.’

‘They’re early,’ said Heriot. ‘And I hope they don’t talk too much, I’m tired of their conversation.’

‘It’s all useful to me,’ Dysart said. ‘Linnet and I get together to exchange notes.’

‘You two!’ Heriot said. ‘Why don’t you just marry and settle down?’

‘It’s her father,’ Dysart said. ‘He wants her to marry Luce, because he thinks Betony and his wife won’t have children, and one day there might be the chance for Linnet to be Queen of Hoad. But Luce won’t agree to marry because …’ His voice faded. He looked around almost as if he thought the walls might turn treacherous.

‘Because Luce thinks that he will challenge Carlyon and become Hero,’ said Heriot. ‘And though the Hero mustn’t marry, he can probably have any woman he chooses.’

Dysart looked up and down the hall through which they were now striding. When he spoke it was almost in a whisper. ‘Things like that are meant to be muttered out in your orchard, not shouted between these walls. Someone might listen to the echoes. So let’s talk about these Lords from the Islands. My father doesn’t trust them. The Islands are restless, though what they would do if they broke away from Hoad I don’t know. Go back to fishing, I suppose.’

For the rest of the morning Heriot sat at the King’s elbow, listening to requests for money and attention registered by the Lords. The King leaned back in his throne, which seemed to wind itself around him, holding him in an embrace of gold and crimson becoming not simply a place for him to sit, but a frame for him. On his right hand Betony yawned visibly, worrying his thumb nail in between yawns. On his left sat Luce, staring at Carlyon. When at last the Island Lords retreated, bowing and smiling, the King turned, not towards his son, but towards Heriot. Heriot recognised the summons in the King’s glance. He took a deep breath and stepped forw

ard.

‘Well, Magician! Were they speaking the truth?’

Heriot moved restlessly, hating this question, which was one he had to answer over and over again.

‘Mostly they spoke the truth, Your Majesty. I’m not perfect in the way I read minds but …’

‘You tell us that every day,’ the King said. ‘Forget your shortcomings. Use your skills to give what impressions you can.’

‘There was a lot they didn’t tell,’ said Heriot. He hesitated. ‘They’ve had a noble from the Dannorad staying on Cresca with Lord Summel and they talked about their old relationship I think, but I can’t be sure. And the image of Lord Summel was moving in all their minds, like a spirit swimming in wave after wave.’

Heriot heard a curious murmur of fulfilled suspicion scuttling around the room as he spoke. Lord Summel was a hero in the Islands but a declared enemy of Hoad.

‘They protected themselves as well as they could,’ he added. ‘These days they try to train the men who sit in front of Your Majesty to present blank minds to your Magician.’

‘Do you think the Lords of the Islands are plotting to change their loyalty?’ the King asked.

Once again Heriot hesitated. Then he sighed. ‘It’s dancing in their minds.’

‘Ah!’ said the King. ‘We will think about this.’ He turned away from Heriot, looking to Carlyon and murmuring to him inaudibly, while Heriot moved back to stand beside Dysart again. The King looked out into the room. ‘The day’s business is concluded,’ he announced.

The Lords of his Council began to stand, but suddenly a clear voice cut into the air of the council room. ‘Your Majesty! Your Magnificence, Lord Carlyon, Hero of Hoad.’

Every head in the room turned, Luce had not only risen from his chair, but had stepped forward to stand in front of Carlyon. Carlyon, at once alert, looked up at him with a smile that suggested he already knew just what Luce was about to say.

Shock Forest and other magical stories

Shock Forest and other magical stories The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom

The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom Aliens In The Family

Aliens In The Family The Magician of Hoad

The Magician of Hoad Twenty-Four Hours

Twenty-Four Hours The Gargling Gorilla

The Gargling Gorilla Kaitangata Twitch

Kaitangata Twitch Heriot

Heriot The Changeover

The Changeover