- Home

- Margaret Mahy

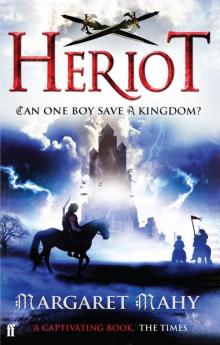

Heriot Page 16

Heriot Read online

Page 16

‘When I saw Izachel the other night, the magic man and the farmer ran together, and I became a single man – the completed one I should be – just for a little. Then Dysart grabbed my arm, and gave me back his promise and …’ Heriot gave his familiar shrug … ‘I must have tumbled in two again.’

Linnet wasn’t interested in Heriot’s puzzling. ‘Stop thinking about yourself all the time,’ she cried impatiently. ‘I’m here about Dysart.’

‘I want to stop thinking about myself,’ Heriot declared, frowning and staring into the dark air. ‘But you can’t, when Kings and Princes are watching you, ordering you to do what they tell you to do, offering a sort of glory, asking for kingdoms and hooking you out of yourself. You have to wonder what you really are. Why did Lord Glass come looking for me? Why was I stolen away from my family where I was happy and driven into Diamond? I have a family – brothers, a sister, a mother, cousins. I’ve got a great-great-aunt. I had to leave them all behind me.’

‘I don’t know anything about that,’ said Linnet impatiently.

‘But if it had all happened to you, you’d start thinking about yourself, right?’ said Heriot quietly.

Linnet sighed with weariness and exasperation. They stared at each other across the candle flame. Somehow Heriot had grown easier. He pushed the hay well back from the candle, then, smiling, he slid his pack of cards from his pocket, and began shuffling them idly, watching the stiff images eclipse one another on the face of the pack. Suddenly he seemed at home in this cage, almost contented as he leaned easily against the back wall of his cage.

‘So what was it you wanted exactly?’ he asked her. ‘You’re not here out of curiosity.’

Something new had come into the glance he directed at her. His smile was unexpectedly familiar. Confronted with that knowing smile, she suddenly found it difficult to talk about Dysart.

‘There’s no need for you to put yourself into a cage,’ she said crossly.

‘There’s every need,’ said Heriot. ‘I’m a good monster. Aren’t I?’ he added, leaning forward a little. His eyes, looking at her across the cards, widened briefly and alarmingly.

‘Nobody thinks you’re a monster,’ Linnet told him impatiently.

‘Everyone does, deep down,’ said Heriot, ‘and so do you.’

‘You can walk out of this cage at any time you want to,’ she said. ‘It’s just a game to you.’ All the same, she thought that Heriot might quickly become crazy enough to insist his game was a reality, and spend the rest of his life in a cage with an open door.

She passed her hand to and fro across the candle flame, making a series of little eclipses. ‘They say the Hero told a strange story this morning,’ she said at last. ‘He told the council he once tried to kill you.’

‘Oh that,’ said Heriot, rubbing his ribs. ‘Ages back. One good thing about my life, it’s never been boring.’ He looked at her directly. ‘Did he say why? Everyone thinks I know everything, but I don’t. I’ve always wanted to know. Carlyon was as sweet as pie to me one moment back then, hiding me from Lord Glass and Cloud. And then, suddenly, he pulled a knife on me.’

‘He says he was thinking treason,’ Linnet explained. ‘He says you read his thoughts.’

Heriot sighed. ‘He was unhappy,’ he said at last. ‘Dark with misery. Is it treachery to be unhappy in Hoad? Then they should hang me. You too.’

‘He said it was treason,’ Linnet repeated. ‘He said he acted on impulse.’

‘Some impulse …’ Heriot muttered, looking back at his cards. ‘Yes, he tried to kill me but I saved myself. And then I ran like a little rat to hide in Diamond.’

‘Why didn’t you tell them?’ Linnet asked. ‘The King might have been on your side.’

Heriot laughed unexpectedly, and held his cards out at arm’s length.

‘Let Dysart go!’ said Linnet, able to say at last what she had come to say in the first place.

‘What do you mean, let him go? I haven’t got him.’

‘He’s lying on his bed in the Tower of the Crow,’ she cried. ‘He can’t see or hear. He can’t move.’

Heriot looked at her incredulously. ‘You think I’ve put him under a spell?’

‘Haven’t you?’ she asked.

‘No.’ The familiar, and somehow disturbing, expression was creeping across his face again. ‘He touched me, back when I wasn’t safe, but –’ Heriot hesitated. ‘Well, if he’s lying there,’ he said at last, ‘perhaps it’s because deep down he doesn’t want to wake.’

‘Can’t you do something for him?’ she persisted. ‘Bring his true life back to him?’

‘Yes, if I knew where he kept his true life,’ Heriot said scornfully. ‘But he doesn’t know himself, does he? His true life shifts around in him.’

He looked down at his cards, then up again, very slowly, this time, up at Linnet once more, staring at her with an expression she could only describe as mischievous.

‘Look at me!’ he commanded. Light oozed out of him like sweat, and she saw his face, clearly for the first time, looking out of its tangled hair, colourless and wild in this light, eyes like pits. He held a card towards her.

‘Now look here!’ he commanded. ‘Look hard!’

Linnet frowned at the picture.

‘Dies heart!’ said Heriot, his voice distant, and, from just beyond the card, he looked to Linnet like a smiling demon. ‘Dice heart! Dysart!’

Suddenly Linnet found she was kneeling, peering almost into the card as if it were a fortune teller’s mirror. Time had been stolen from her life. She could feel the discontinuity, knew something had happened but had no idea what it might have been. She had been given an instruction. It was there in her head, her feelings and intentions aligning themselves around it, but she had no idea what it was.

‘What have you done?’ she cried, shivering.

Heriot replied with a question. ‘What does it feel like?’

‘A break!’ said Linnet, forcing herself to speak with all the detachment she could muster. She wasn’t going to gratify him by showing fear. ‘As if I’d gone out of existence for two minutes and then flashed back on again, the same but different.’

‘That’s what I feel like from time to time,’ Heriot said, sounding surprised and suddenly companionable. ‘The same but different.’ Then he leaned forward, his dark eyes openly alight with the mischief she had glimpsed earlier, and touched her lightly but somehow powerfully on her right cheek. ‘On your way!’ he said, still smiling.

Linnet mistrusted that smile. ‘What did you do?’ she asked, rising, vaguely aware of a slow warmth spreading through her, a curious spasm of excitement in the pit of her stomach. Why was she getting to her feet and moving to the door? Nothing had been accomplished. Dysart was not saved.

‘Goodbye!’ Heriot said, lying back and shutting his eyes. ‘And do call again soon.’

‘What did you do to me?’ she asked once more, looking back over her shoulder.

‘It’s a riddle,’ Heriot said. ‘You lot and your kingdoms!’ he added, turning his back on Linnet, pulling his knees up, bending his head down, curling himself and laughing in his own darkness. ‘You’ll find out! Dysart! Yes! Meanwhile I’ll get some sleep.’

His gentle laughter terrified Linnet. She scrambled away from him out of the unlocked cage and into the gardens through which she had felt her way so blindly only an hour earlier. The familiar stars had curved a little across the sky, but the garden seemed to be springing up around her in lines of light, things flaring into existence as she passed them, then dying back into darkness as she left them behind. Yet this flaring was not a flaring of light. Somehow she was perceiving the world by the residues of its history.

She turned towards the Swan Tower, but found herself brought to a standstill as if she’d lost her way, though she knew exactly where she was. Then, slowly, she turned to look sideways towards the Tower of the Crow. Light came from a torch burning over the doorway, and there, by a little brazier beside the door, she cou

ld see a group of men talking in low voices, glancing upwards from time to time, no doubt gossiping about Betony’s wedding, about Heriot and Dysart, and all that had happened around them. If there had been only one guard she might have walked up and demanded admittance, but it didn’t seem possible to show herself to a whole crowd, and walk past them into the Prince’s Tower.

Linnet looked up to the very top of the tower. That’s where I should be, she thought to herself.

The tower rose into the night, dwarfing the patch of light at its own doorway, and then, as she frowned to herself, measuring its height, ascending hyphens of dim light, one above the other, seemed to ooze towards her from its blank surface. She was reminded of notes on a page of music, recording a rising scale. It took her a moment to realise what a freak of starlight was showing her. There before her, seen more clearly than ever before, was an ancient, exterior flight of steps, similar to those that wound around the Tower of the Swan, but even more worn and crumbling.

Unseen by the men at the door, Linnet crossed the bridge of the Crow, slipped along a thin path to trees and bushes at the base of the tower, then twisted herself, as silently as possible, through leaves and twigs until, at last, she laid her hand on the wall of the tower, felt the deep chill of the blocks of stone, and there, under her palm, very faintly, the actual curve of the tower’s side. She even imagined it might be breathing.

Sliding sideways, she searched for what, in due course, she found … a first step. Finding it so easily filled her with such excitement and determination that she had no room for ordinary fear. She was terrified at her own plan, and yet it was an exalted terror … a terror that was also a necessity … a terror she could somehow enjoy.

She felt above the first step, and found another one and then another, but they were unclimbable, or so she thought at first. But then her blind hand, circling up and around, discovered, almost as if it had known just what was there to be found, a short crescent of steel set in the stone, a handhold. After only a second of hesitation, Linnet put her foot on the first step of the crumbling stair, locked the fingers of one hand around the steel bar, then felt for the one which must surely be above it. She began to climb, rising high into the airy night.

Her first steps were desperate ones. ‘I can’t do this,’ she thought wildly, but doing it, nevertheless. ‘I really can’t do this.’ Experimentally she faced the stone, then flattened herself against it, finding herself almost spreadeagled, arms stretching desperately from handhold to handhold. Feeling sideways with her foot, she stepped again, trusting her weight to the next stone, and then to other stones, some of which accommodated only her toes and the ball of her foot, and left her heel treading air. ‘I can’t do this, but I’m doing it. I’m on my way.’ She breathed in the dust and grit of the weathering stone … felt the very substance of Guard-on-the-Rock filling her lungs as she hung in darkness. More than once she stepped on the hem of her own cluttering dress.

Once a step wobbled like a loose tooth in the face of the tower, and she tilted backwards. ‘Falling!’ she thought, growing sick with fear as one of her shoes tumbled away into the night. But the air around her grew somehow hard and unrelenting; she found an impossible purchase in it, and pulled herself forward again. As she did, she felt a tenuous but determined presence collecting itself around her, and knew at last exactly what Dysart had meant when he had talked, years ago, about someone being there to catch him.

After this, she climbed carefully yet with increasing confidence, believing she was protected too. She had no fear that gossiping men at the main door of the tower might hear something scrabbling overhead, and look up to see her struggling upwards, in the dark. Though she hated the emptiness at her back and the way in which night gaped over her, eager to take her into itself, she closed her eyes and came to feel she was climbing, not just the side of the tower, but across the face of the night. A little later, she had the odd feeling the castle was sinking beneath her, rather than that she was rising up its side. The steps led her past Luce’s windows, which were dark, for Luce was in the rooms at the base of the Tower of the Hero, singing battle songs with his campaigner friends, and watching Carlyon with an altered expression, more openly predatory than ever before. Increasingly the rim towards which Linnet struggled appeared to be gilded in starlight, but before she reached that rim she realised she would be passing a window that must be the window of Dysart’s room.

Though it had been invisible from the ground, she could now see the room was faintly lighted. Step up and step up again. She was able to look in, her eyes just a little above the plain edge of the window, and see Dysart lying on his bed. Two men were looking down at him, one of them Dr Feo. As she watched they straightened the covers of wool and fur over Dysart, and left the room, as if someone had called them away. Candles burned in tall holders on either side of Dysart, who looked as if he had been laid out for burial.

At last, Linnet’s groping fingers found a ridged edge. At last she hauled herself up on to a windowsill, wide enough for her to sit high above the city and catch her breath. Then she swung her quivering legs sideways and thumped forward into a space that was unexpectedly familiar territory, for it was almost a twin to her own space at the top of the Tower of the Swan. Her fingers and leg muscles immediately cramped, so that the first minutes after her climb were spent struggling with pain, and trying not to cry out, though a few protesting groans forced their way through her clenched teeth.

But, even as she fought to stretch her muscles into obedience, she was warmed by a great blush of triumph. She was there … safely there. Her leg muscles grew loose. Her fingers, knotted like a bundle of twigs by the cramp, became their lively, separate selves again. Linnet stood, stretched, walked around, trying to stamp a continuous trembling out of her knees and ankles, then moved to a square opening, which gave on to an inner stair that corkscrewed into darkness, down through the heart of the tower. The darkness was not complete. Light was seeping from somewhere below her. She turned her back on it and tiptoed towards Dysart’s bed. I mustn’t hesitate, she thought. I’m protected, she reminded herself.

Within a minute, she was looking down on Dysart. He lay on his side, flanked by candles, his eyes closed, his whole face sealed like the face of a dead man.

‘Dysart!’ she said. ‘Dysart!’ She touched his face, and then, when he did not wake, she looked, with puzzled wonder, around the room in which he had spent so much of his life.

It was a small round room. His bed took up most of the available space. At the foot of his bed was the desk. In the wall beside his desk was the window through which she had climbed, crossing the very windowsill where once some vagrant, disconnected part of Heriot had sat, watching over Dysart’s childhood, and both threatening and luring him … setting up the moment it would need his friendship, courage and authority.

And here she was, standing in Dysart’s room and looking down at him, while, somewhere in time, she felt she was still on that plain watching him vanish under the hoofs of charging horses. Somewhere beyond the castle, out in the King’s garden, the Magician of Hoad was curled in his cage, and it seemed to Linnet that his head was not so much a head that took up space, but space itself … a curious space into which the real world spiralled like water through a hole, emerging altered in some way, because, as the world went through him, the Magician watched it spinning, and the power of his watching changed everything.

Looking down once more she saw that Dysart’s eyes were suddenly open, and he was staring at her, wide awake and asking her a silent question. And, as their eyes met, she felt once again, the wave of heat, and the disturbance Heriot’s touch on her cheek had transferred to her. Dysart slowly sat up, without taking his eyes from her. Linnet moved a step towards him, touched his cheek as Heriot had touched hers, then, bending like some tall flower gently pushed by a wind no one else could feel, she kissed him.

Dysart put his arms around her and pulled her against him so tightly it was as if he was trying to catch, bet

ween their very bodies, all their misunderstandings and ambitions, all the illusions that had kept them apart. It was as though he was determined to crush all distractions out of existence. In silence they kissed and kissed and kissed again.

‘In the old story,’ Dysart murmured at last, ‘everyone woke when the lovers kissed.’

‘In this story everyone sleeps,’ Linnet answered. ‘Everyone except us.’

‘I’ve always been mad, but I didn’t know that I was a fool as well – not until now. Linnet, I love you.’

‘And I love you,’ she replied, ‘and I’m the fool. I’m promised to Luce. I’m signed and sealed.’

‘Our fathers signed,’ said Dysart, and, speaking from the narrow confines of his bed, he made it sound simple. ‘We tell them … declare ourselves … and then we hold to it. Hold to each other and forget Hagen!’

‘Forget Hoad!’ she replied, laughing.

He didn’t argue. He nodded. Then he put his arms around her again. She was cocooned in the heavy folds of her dress, cold from the outside air, her back to the candle and her face in shadow, whereas his was lighted. Sliding her hand from his shoulder, she tucked it behind his head, drew his face towards hers and they kissed yet again.

‘We’ve signed now,’ she said, then sighed and leaned against him like someone yielding up a heavy burden to a fellow traveller who was somehow fresher and better able to carry it for a while.

‘So you’ll marry me!’ he said, in the reflective voice he used when committing something to memory.

‘But are you allowed to marry twice over? You’re already married to your city,’ Linnet answered, surprised to hear a little melancholy along with mockery in her own voice.

‘Oh that!’ Dysart replied, debating. ‘Well, my father gave up his first marriage … gave up love, that is … to take on Diamond. I’ll divorce Diamond and take on love. If we do things backwards we just might unknot the past.’

Far out, many leagues beyond what anyone in Diamond could see, far out in distant Hagen, the volcano sighed out dark smoke, unseen in the greater darkness, while the calm eyes of the glacial lakes looked through the mountain forests towards the stars. But Dysart and Linnet didn’t think of brothers, Magicians, Hoad or Hagen. They clung together, kissing in the room at the top of the tower, with the fidgety castle below them, the restless city and the land of Hoad around them, and windy darkness encompassing the world.

Shock Forest and other magical stories

Shock Forest and other magical stories The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom

The Riddle of the Frozen Phantom Aliens In The Family

Aliens In The Family The Magician of Hoad

The Magician of Hoad Twenty-Four Hours

Twenty-Four Hours The Gargling Gorilla

The Gargling Gorilla Kaitangata Twitch

Kaitangata Twitch Heriot

Heriot The Changeover

The Changeover